DURING a Facebook live-stream, in August 2023, Shawn Fain, President of the United Auto Workers, tosses a crumpled piece of paper through the air, landing it in a waste basket. “It is trash,” he declares, referring to the latest contract offer from the automaker once known as Chrysler, now rebranded as Stellantis, “so that is where it belongs.”

A month later, under Fain’s leadership, the UAW which represents 145,000 autoworkers began a historic trilateral strike against the “Big Three” automotive manufactures, Ford Motor Company, General Motors and Stellantis.

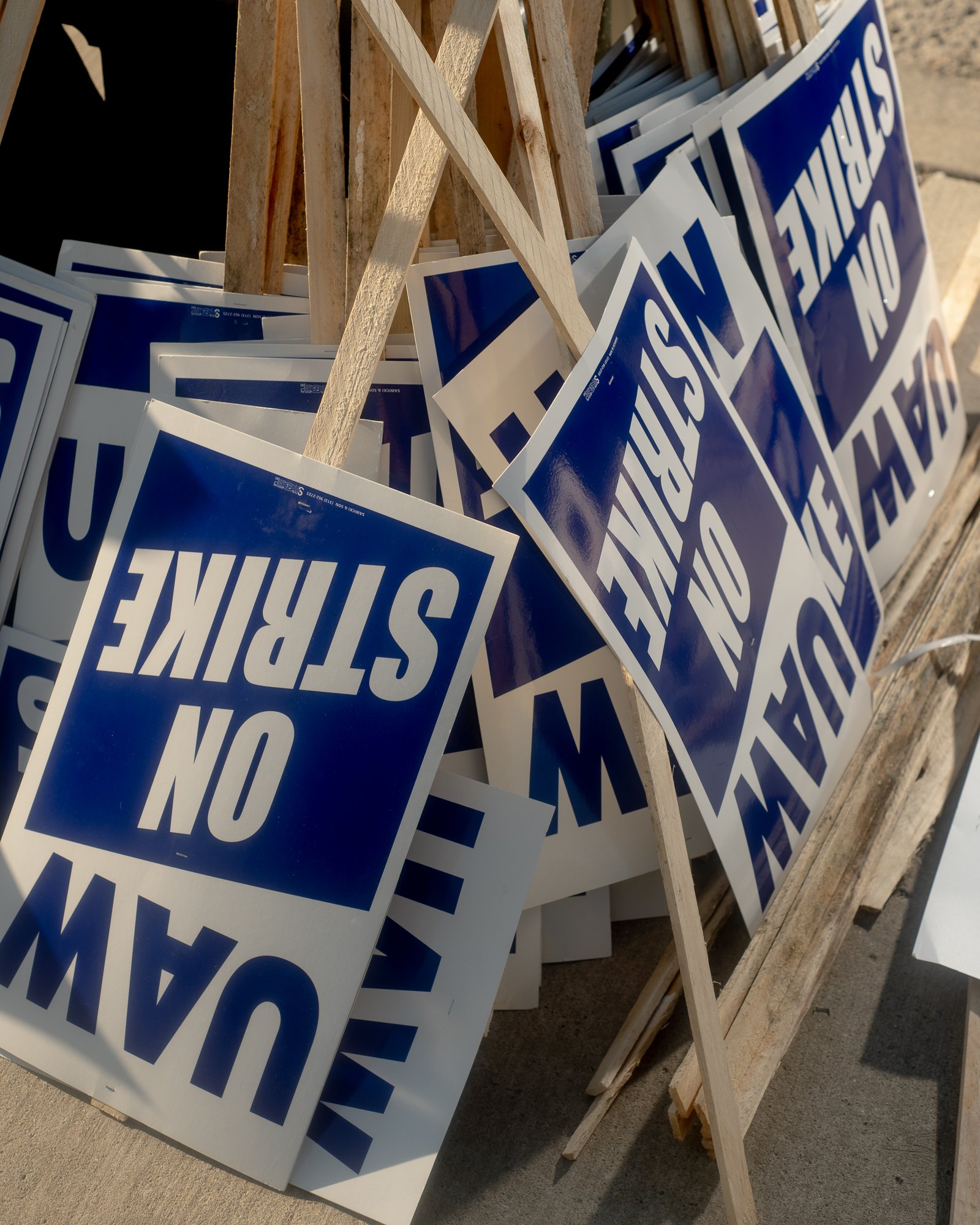

The fight was on. After decades of rising economic inequality and years of skyrocketing corporate profits, the UAW was “standing up”. The rallying cry was for elevated wages, a condensed four-day work week, and the cessation of the tiered wage system that placed new workers at a significant financial disadvantage. The tactic was to strike all three unionized auto-companies at once, at various plants and factories, utilizing surprise and

detailed organizing. In the decade that followed the Great Recession, the UAW’s reputation was marred by scandal, corruption, and a perception of coziness with automotive CEOs. After a six week siege, Fain’s UAW proved those days were over. Their slogan was “record profits for corporations mean record contracts for workers,” which, in a major win for organized labor, the union delivered.

The agreements include substantial wage increases for all Big Three members, life-changing raises for tens of thousands of members, and tens of billions of dollars in product and investment commitments from the companies. Following decades of deindustrialization and the decline of the middle class, these new contracts mark the dawn of a future characterized by re-industrialization and enhanced labor rights. This transformative path forward comes amidst challenges posed by artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, as well as a critical examination of the vulnerability inherent in “just in time” globalized supply chains.

To witness this win and to see the subsequent motivation for more union drives in non-union factories has been deeply inspiring for me. Labor rights loomed large over my upbringing in Allen Park, Michigan. My father has spent his career as a lawyer at the UAW Legal Services, a benefit for UAW members which provide free legal aid. Throughout my life, he would tell me about his daily load of cases and clients, many of whom faced bankruptcy or other financial perils. I understood these situations to be unjust rewards for a lifetime of honest work. It brings me great pride that my father spent his career working in a law office that fights for working people. My own photographic work is inspired by the tradition he taught me — to do what you can for who you can with respect and shared dignity.

Another impactful figure in my life was Cliff, the father of my childhood best friend Evan. Cliff dedicated his career to Ford, steadily ascending the ranks to the esteemed position of finishing inspector—a role he continues to excel in well beyond the conventional retirement age. Each summer, he would take Evan and I, along with as many other boys as he could jam into his Ford Explorer, to Portage Lake for camping, tubing, fishing, and wakeboarding. Cliff, one of the most intelligent individuals I knew growing up, seemed capable of fixing or diagnosing any issue with a neighbor’s car, discussing the intricacies of socio-economic issues during the ‘08 recession, or constructing various skateboard ramps for us to enjoy. His actions and way of life made the significance of a union job and the security it could offer for living a comfortable middle-class life crystal clear.

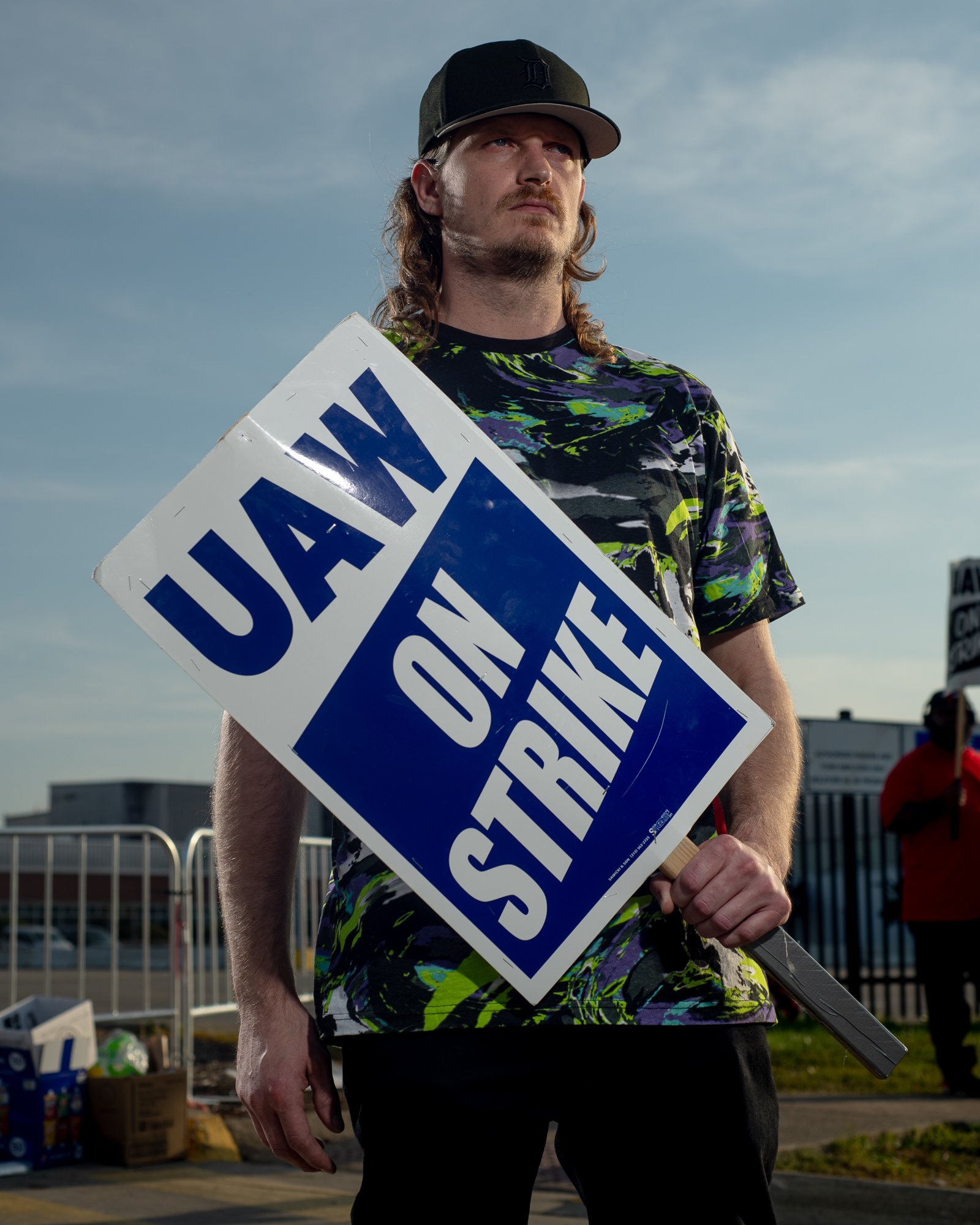

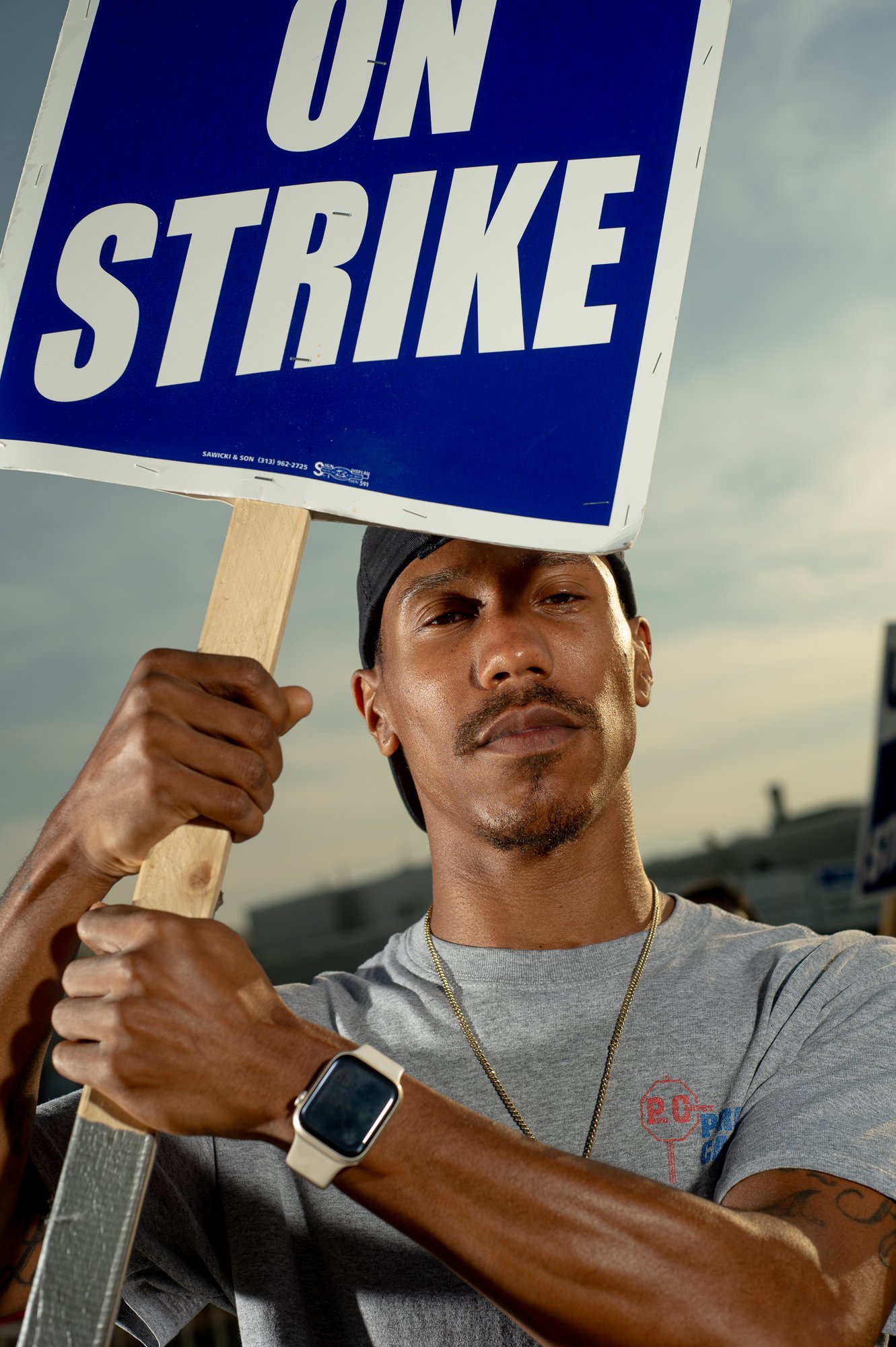

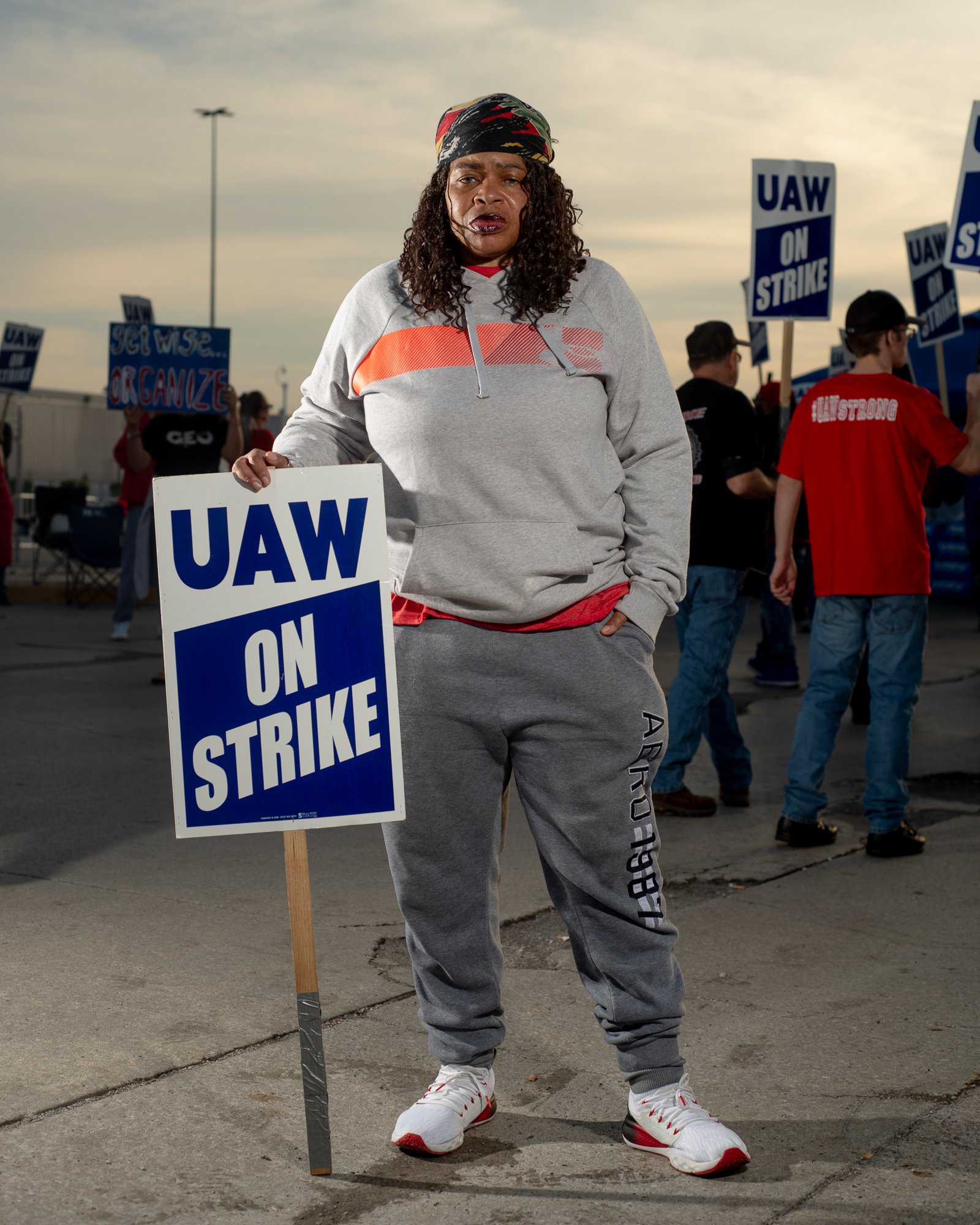

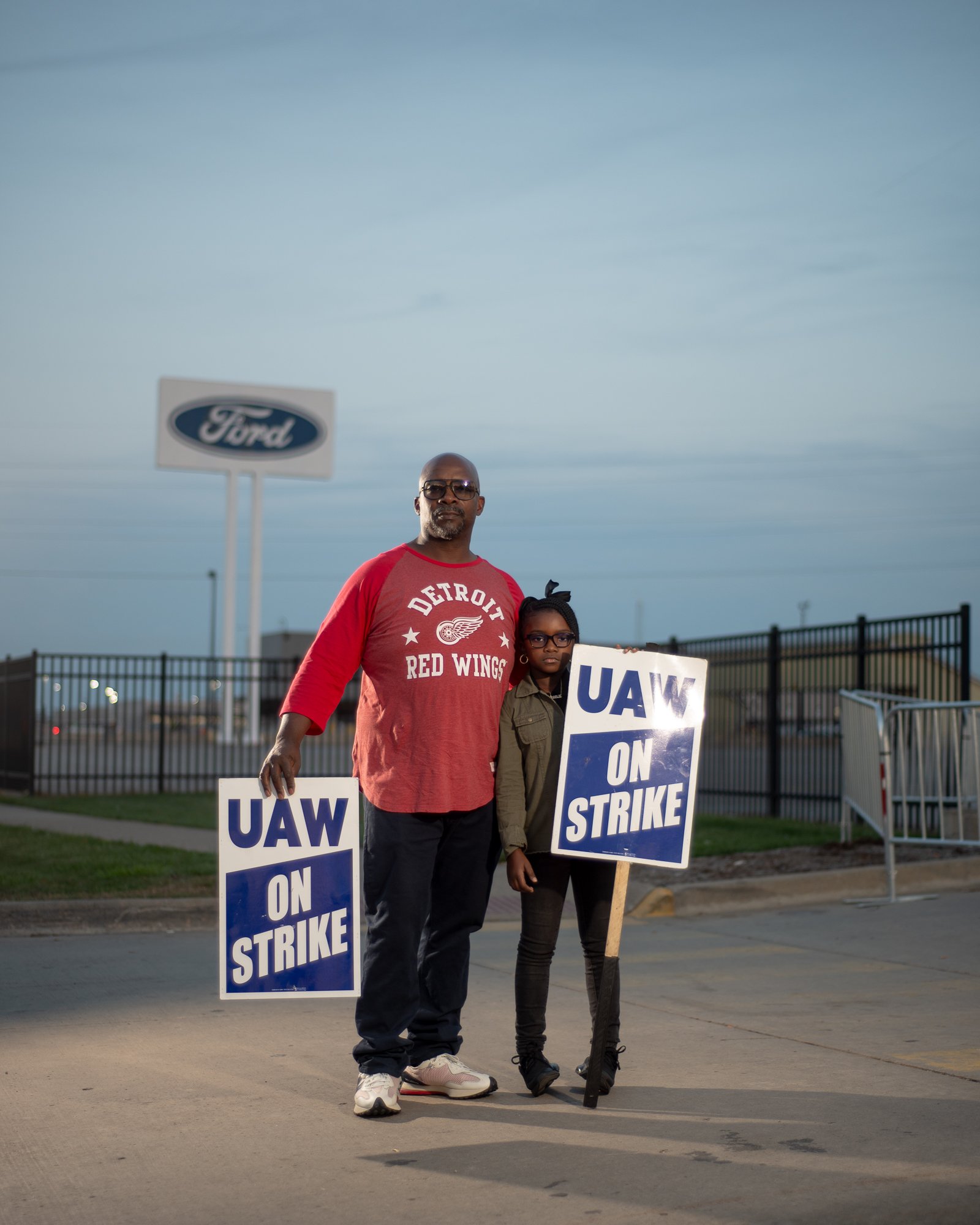

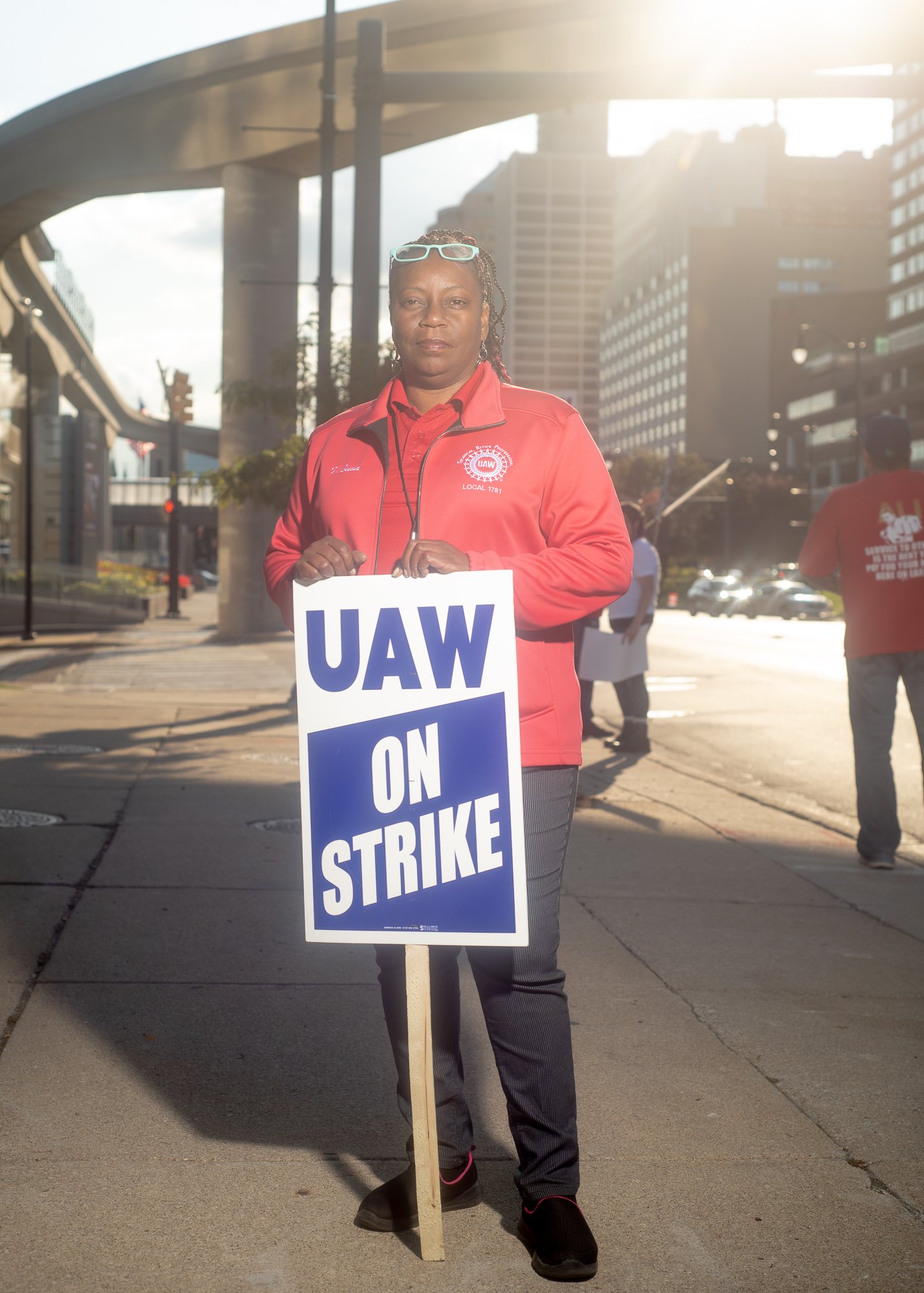

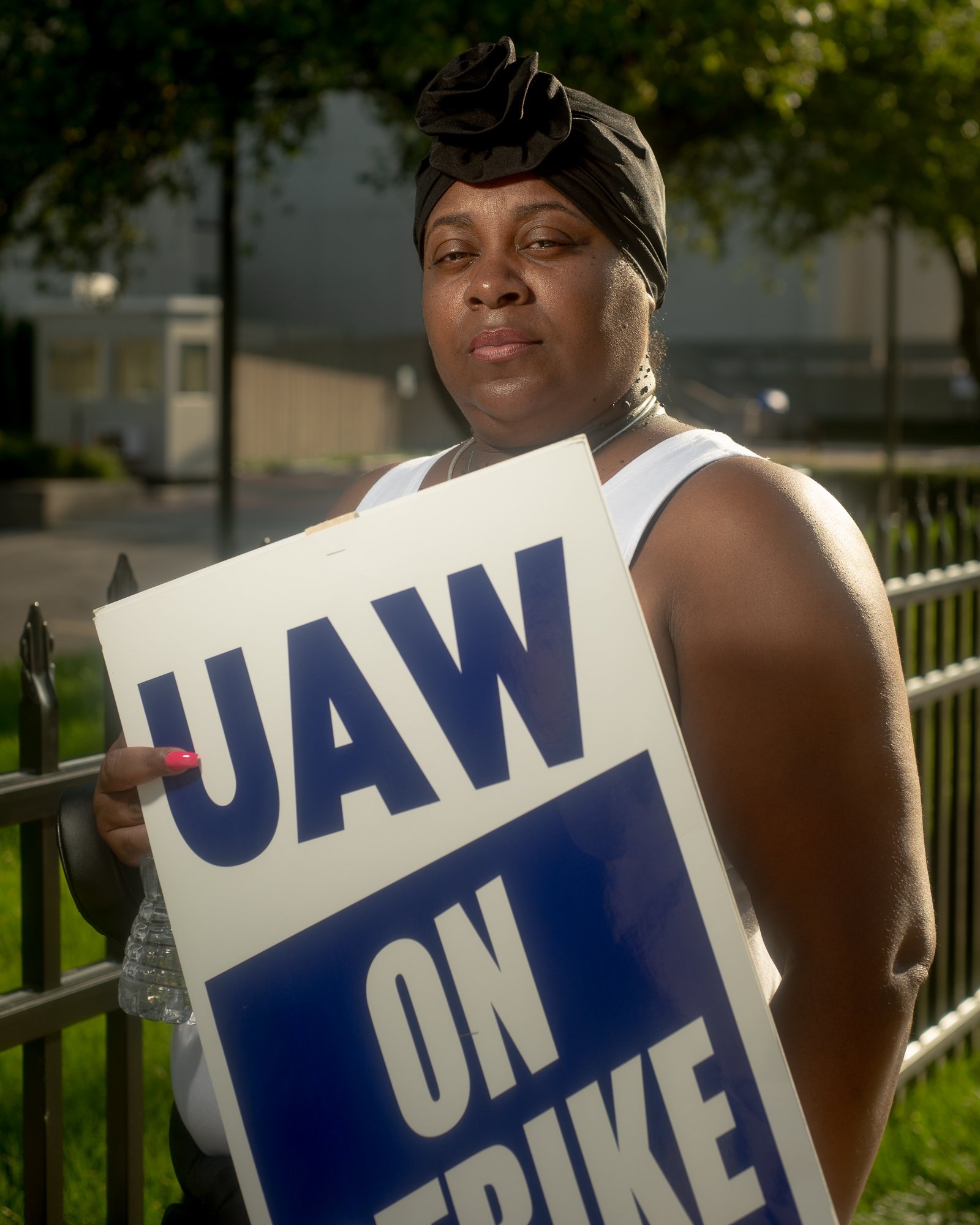

The environmental portrait photographer Shelby Lee Adams once said “My greatest fear as a photographer is to look into the eyes of my subject and not see my reflection.” This resonates with me. As a documentarian, I consciously avoid strict objectivity, recognizing that every storyteller injects their own biases and framing into a narrative. My goal was to attend the picket lines, rallies and marches during the strike in order to witness history. Among those photographed are single mothers who worked multiple jobs on top of their automotive jobs to support their families, young men hailing from generations of autoworkers who face indignant tiered pay and a ‘permanently temporary’ employment status, and labor elders, whose calloused hands held signs in support of the next generation of workers.

Shortly after the UAW’s contracts were inked, General Motors said it would issue a $10 billion share buyback and 33% dividend increase — a salve for investors and blatant proof that as much as the industry and some media outlets tried to cast workers as lazy and greedy, the companies had capital and plenty of it. However, instead of making a long term investment in their workforce or research into emergent technologies the corporations would rather focus on short term gains for shareholders. This short term thinking, neoliberal strategy accomplishes nothing except for enriching the wealthiest among us during an era of unprecedented wealth division and a declining middle class. As the UAW gears up to support union drives in the south, perhaps a long term mindset will be taking place somewhere in the industry. For now, we can celebrate a win for workers.

Niki Williams

Detroit, December 2023